Upgrade Your Gut

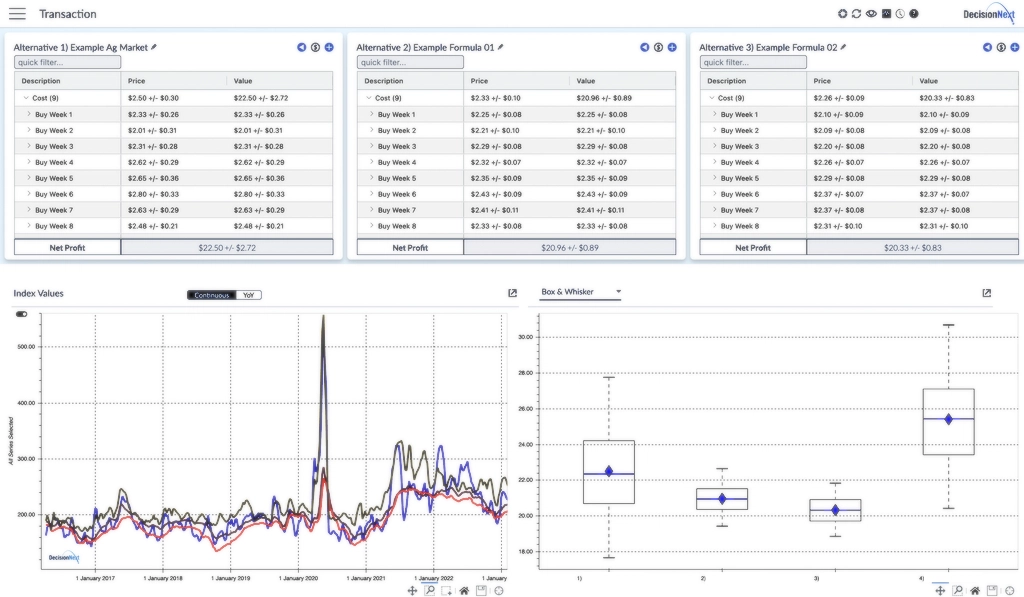

Strengthen and optimize your position within rapidly changing commodity markets with the help of cutting-edge predictive analytics. DecisionNext’s advanced AI-powered software suite provides best-in-class econometric tools for optimal risk management and decision-making in virtually any natural resource or agricultural market, traded or non-traded.

Get the best data on the market

Enjoy faster access to dynamic data and fuse it with your own

Utilize the best out-of-the-box models

Improve forecast accuracy with our curated AI-forecast models

Make the best decisions every time

Quantify risk for better informed business decisions

Boost profit and manage risk

Enhance decisions with consistency and repeatability

DecisionNext is a best-in-class AI platform that empowers companies to buy or sell at the best times, with the best formulas, at the best prices.

Built in collaboration with our customers, DecisionNext has revolutionized how price and supply forecasting can improve business decisions. And it is the only platform that incorporates users’ wisdom in its algorithms!

DecisionNext is a proud AWS Partner and you can now find our solutions in AWS Partner Portal. Contact us today to learn more.

Our Commodity Expertise

Our suite of tools provides a proven formula for best in class decision making for virtually any commodity in natural resources and agriculture, traded or non-traded.

Food & Agriculture

Beef

Pork

Poultry

Dairy

Grains

Edible Oils

and more...

Natural Resources

Iron Ore

Thermal Coal

Liquid Natural Gas

Copper

Nickel

Zinc

Shipping

and more...

Case Studies

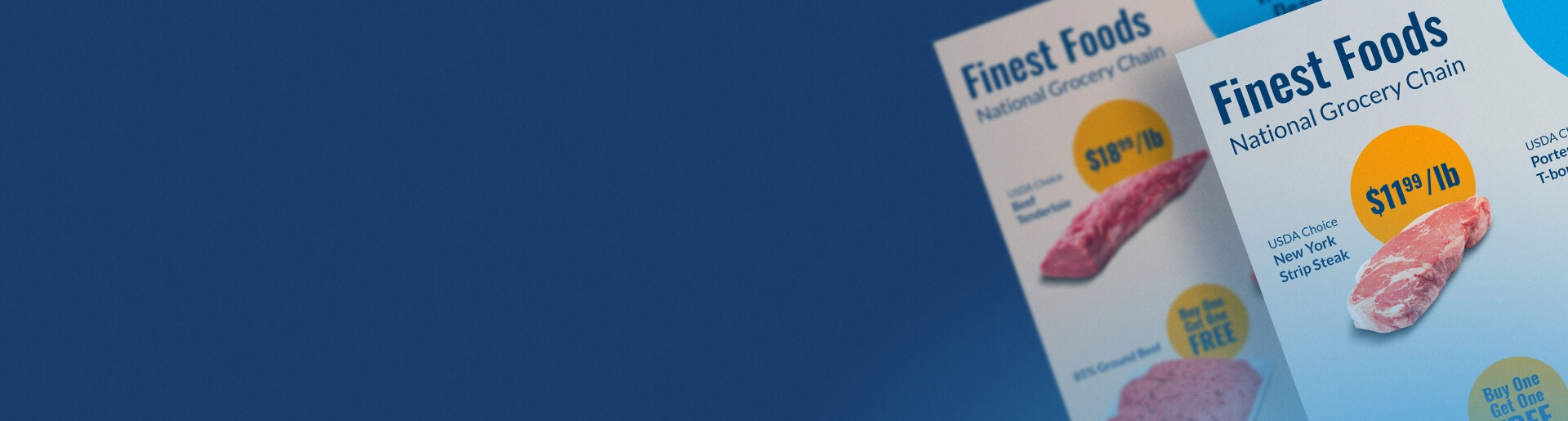

Increase Ad Plan Margin by 6% with DecisionNext

Introducing an innovative way for the industry to forecast beef prices.

You're in Good Company

Here are some of our amazing customers.

Don't Take Our Word For It

Here's what our customers are saying.

Can the other guys really leverage the power of AI to minimize risk and maximize gain? DecisionNext does.

See how our AI-driven platform checks all the boxes.

SWIPE to compare

| DecisionNext | Free Data Aggregators | Paid Data Aggregators | Data Analyzer | Consulting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | $$$ | $0 | $$ | $$ | $$$ |

| Commodity Types | |||||

| Food & Agriculture |

|

|

|

|

|

| Natural Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

| Forecast Capability | |||||

| Forecasting Centralized Database |

|

|

|

|

|

| Periodic Forecasts |

|

|

|

||

| Daily On-demand Forecast Updates |

|

||||

| Weekly Outlooks up to 18 Months Out |

|

||||

| Automatically Track Accuracy |

|

||||

| Quantified Uncertainty |

|

||||

| Decision Support Tool | |||||

| Optimal Deal Structuring |

|

||||

| Forecasted Least Cost Formulation |

|

||||

| Forecasted Raw Material Utilization |

|

||||

| Proactive Risk Forecasting |

|

||||

| "What If" Analysis Tool | |||||

| Patented Expert Opinion Methodology |

|

||||

| Causal Fundamentals Analysis |

|

||||

Food for Thought

A collection of thought leadership, case studies, interviews and more.

Featured

Whetstone Distribution Partners with DecisionNext to Enhance Protein Price Forecasting

SAN FRANCISCO, California – January 20, 2026 – DecisionNext, the leading AI platform that helps companies optimize commodity buying and selling decisions, today announced …

Read Article

The DecisionNext Finished Goods Index Report | January 2026

Key Insights The Finished Goods Index has rolled its base year from 2024 to 2025 Cheeseburger prices are projected to rebound toward 2025 highs by summer Hot Dog index …

Read Article

FGI Methodology Update

With the start of 2026, DecisionNext has officially updated the base year used in its monthly Finished Goods Index Report, transitioning from 2024 to 2025. This rollover …

Read Article

Rising Dairy Herd Pressures U.S. Butter Prices

One of the major stories in dairy markets across 2025 was the precipitous fall in butter prices. For buyers, this kind of move can quickly reset negotiation leverage and …

Read ArticleSign up for our Newsletter: The Formula

The Formula is DecisionNext’s monthly newsletter for industry insights, product updates, company news and more!

Connect the Dots

Get in touch with us to learn more about our solutions and the work we do.