Dr. David Boussios is the economist driving our teams to leverage data to find answers to complex market problems. In the first of this two-part Chicken Pricing series, David dives deep into this booming industry and helps us to better understand how it all works.

The Global Chicken Industry Continues to Rise

For the last 10 years, the consumption of broiler chickens in the United States has consistently increased. The latest estimates indicate that people eat 100.7 pounds of chicken per person per year. (That’s a lot of chicken!) This is only slightly lower than the combined consumption of beef (57.3 pounds) and pork (49.6 pounds) per person per year.

Chicken is the most vertically integrated and automated of the protein markets. Compared to a finished steer (eighteen months) or a finished hog (six months), the timespan for a broiler chicken is much shorter, at just six to seven weeks. This shorter period along with environmentally controlled broiler houses, means fewer unexpected shocks can occur from hatching to processing. And since it’s the most prescriptive of all domestic meat markets, you get a much more formula-oriented modeling process.

Private Data is Kept Private, but Not the Only Game in Town

Unlike beef or pork, there’s no mandatory price reporting for whole bird values or chicken parts. It’s all voluntary. As a result, private sources for chicken prices have become industry standard. (Think Urner Barry, Agri Stats, Express Markets Inc., etc.), though they are not the only game in town.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) publishes publicly available chicken price data weekly. The USDA’s collection and reporting process is explained and defined, as opposed to some private sources. The USDA uses what’s called a double-verification process to ensure data quality. In practice, the double-verification process means the USDA will speak with a buyer and request a report on recent trades. They then go to that product’s seller and request the price and volume information for the same trade. Only if the price is confirmed independently by both parties is that data added to the USDA record.

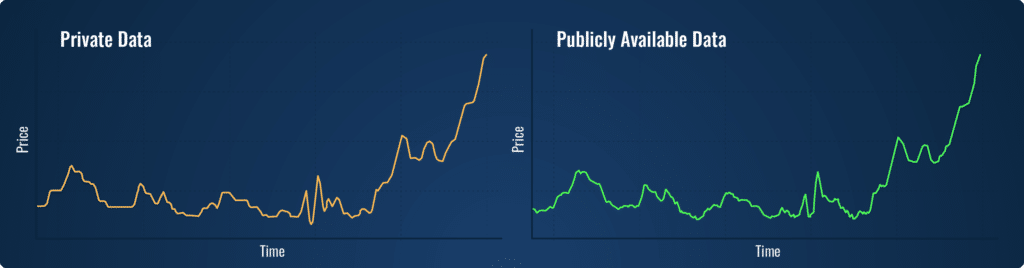

The double-verification process for voluntary data likely limits the amount of information that is reported. Buyers are less likely to confirm high prices paid, while sellers may not report low prices received as neither party wants to contribute to price movements that could negatively impact their profits. As such, the double-verification procedure likely results in a smaller survey size when compared to private data reports. That said, the USDA data looks very similar to that of private data sources, see the visual comparison below (Fig. 1):

Figure 1 – Comparing private and public chicken price data

The USDA reports roughly 14 chicken-part series on a weekly basis (Fig. 1). While this is fewer price series than other sources, the USDA covers the major parts of the young bird, regional whole bird, and chicken without giblets (WOG) prices. Relative to private data providers, the USDA doesn’t report extensively on products that have been differentiated, such as cage-free or chicken breasts with specific production attributes requested by a quick service restaurant (QSR) chain.

In some ways, it can make sense to track the differentiated series. This is particularly true when the markets diverge in fundamental ways. However, differentiating price series also leads to smaller market sizes, where prices can be distorted by individual transactions or suppliers.

Broader benchmarks, such as those provided by the USDA, plus premiums and discounts, can provide a useful way to think around small specialized markets, without having to deal with the risk associated with less competitive markets.

Key Takeaways: Comparing USDA and Private reporting

| USDA | Private | |

| Survey/ Reporting Method | Double verification | Unknown |

| Survey volumes | Transparent but small | Unknown |

| Chicken prices | Whole bird and part prices | Whole bird and part prices |

| Geographical differentiated | Some | More |

| Production differentiated | No | Yes |

| Additional information | Data is free and publicly available. | Data is expensive but covers more products, including thin markets. Thin markets are more likely to have distorted prices. |

Conclusion

The world of chicken pricing and forecasting is characterized by a unique landscape. Voluntary reporting prevails. And unlike beef and pork, chicken pricing is not government mandated, so it led to the widespread adoption of independent private reporting.

To ensure great consistency and trustworthiness, the USDA transitioned from regional to standardized national reporting in 2022, with the goal to provide a more comprehensive view into the chicken market. It’s a bit of a moving target, but as the industry continues to grow exponentially, consistency and trustworthiness are key.