How to be a successful investor in mining stocks – a checklist of nine ways that mining companies can make money

Published: December 4, 2015

Introduction

Howard Marks, the well known investor, makes it sound simple: ‘The upshot is simple: to achieve superior investment returns, you have to hold non-consensus views regarding value and they have to be accurate’. But simple is not the same as easy.

Most mining companies today are focused on leveraging infrastructure (that is, expansion) and cutting costs (operating capability). But, as Mine Insider discussed in our recent article ($400 B reasons why the mining industry must change), we don’t think these will drive superior returns for investors.

We favour companies looking at unfashionable ideas: high-leverage acquisitions, smart marketing/trading and low-cost mine developments can all deliver high returns at this stage in the cycle. In future articles, we will come up with some suggestions of counter-cyclical plays. Until then, we think it’s time for a thoughtful industry debate. So we look forward to your feedback and ideas. Do you have some suggestion for mining companies pursuing non-consensus views?

How do mining companies create value?

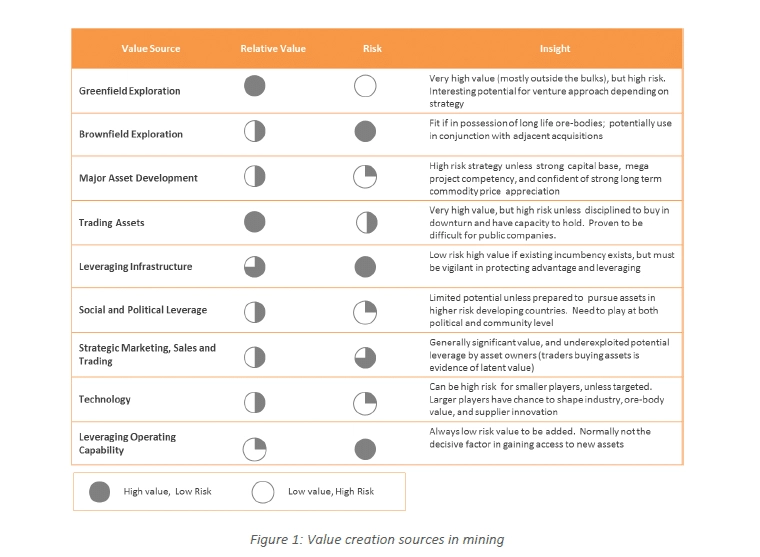

Much can be learnt from how mining companies have created value in the past, and we have outlined in below the broad areas of value creation we typically see in the industry. In interpreting this analysis, two further questions need to be overlaid, firstly what is relevant to a firm’s particular situation, most importantly its existing competencies and assets, and secondly how might value creation opportunities shift due to future trends and events in the external environment.

Before examining sources of value creation, it is necessary to clarify what we mean by value creation in mining. Ultimately value is measured by discounting expected future cash flows, which loosely translates into enterprise value, and then share price after liabilities are accounted for. This definition is broadly accepted; however the complexity lies in the assumptions regarding future cash flows, and the capital investments required to achieve these. This presents two problems. Firstly in mining, most value is ultimately created through subsequent brownfield expansions, but this “option value” is often poorly represented in initial mine valuations. Secondly, Mining is notoriously cyclical, and human beings are universally prone to extrapolation, so expected value is almost always underestimated at low points in the cycle, and overestimated at high points in the cycle (there are plenty of examples from the most recent mining boom). The purpose of pointing out these issues is to highlight that rather than focusing on precise definitions of value, it is probably more beneficial to focus on the uncertainties that arise in mining given their relative impact.

When assessing the sources of value creation potential, it is an axiom that value upside potential comes with value downside potential and the upside and downside are not always symmetrical. However, mining is by definition an industry where incumbent assets are depleted, so calculated risk taking in pursuit of value growth is an unavoidable part of the business, if the business is to be sustained – this is why mining is seen as high risk by investors who look at a broad range of asset classes. The key to successful strategy therefore is not so much about avoiding risk, but is in having the capability to manage the risk associated with chosen growth pathways. For example, if growth is to be through acquisitions, then capital management programs and knowledge of industry cycles are critical, or if growth is to be through managing project developments, then risk management strategies for large capital projects should be a core competency, and so on. Too often businesses are attracted to the value upside associated with a particular growth pathway without the capability, to manage (or worse see) the associated risk.

The value areas are summarized in Figure 1 below in respect of their relative value potential and perceived risk. These assessments are necessarily subjective, and require review once a company’s strategy is more thoroughly analysed. However, several preliminary points can be offered:

- The highest potential pay-off as part of a growth strategy is likely to be asset trades, but this is very high risk without strict adherence to value guidelines, and strong awareness of place in the cycle (which can be obscured by natural psychological biases within the decision making cadre).

- Greenfields exploration is high value, but very high risk activity given the complexity and track record of large projects, with no guaranteed pay-off.

- Access or control of infrastructure is often the key to unlocking value and should be leveraged to generate value at relatively low risk.

- Both brown-field exploration and commercial innovation in marketing represent relatively low risk (cf. Greenfields and asset acquisitions) means of increasing value that should be exploited where incumbent position allows.

- Operations effectiveness remains an important factor in protecting value, but is unlikely to lead to the magnitude of new value creation required for sustained growth.

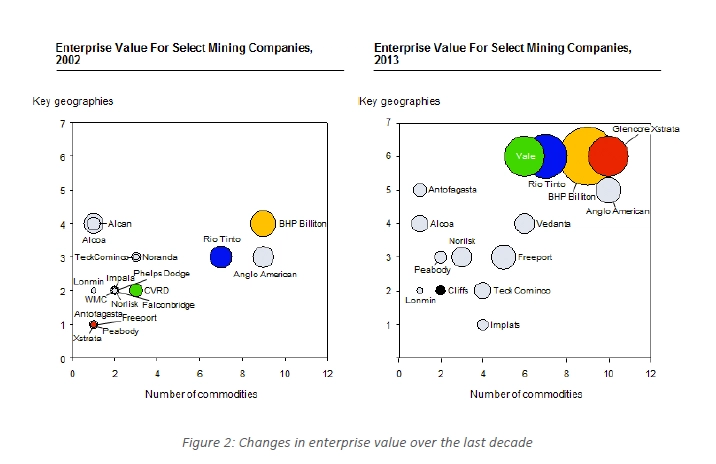

The relative value sources described are not static but are impacted by changes in market and industry trends, and in internal capabilities. A strand-out example of is shown in Figure 2, where the Chinese infrastructure boom dramatically changed the value creation potential of mineral asset acquisitions in the early part of the decade. Glencore-Xstrata, an avid acquirer of assets at the time (in many cases for access to marketing rights) benefited hugely from this value shift.

So the question remains as to how future trends will impact the assessment of potential value sources. Several points can be made. On asset trading: we may well be rapidly approaching the end of the Chinese infrastructure boom, so the opportunity for purchasing quality assets at lower prices could again be approaching, particularly if there is, as there has been in the past, an over correction. On strategic marketing and trading: trading houses and private equity firms are already entering the asset ownership side of the industry, so there is likely to be a shift in activity pertaining to strategic marketing and trading as these entities look for new ways to create value. On technology: the industry has largely been untouched by major technology shifts over the last few decades, but there are signs that change is incipient with many step change technologies starting to mature.

Core principles in mining value creation

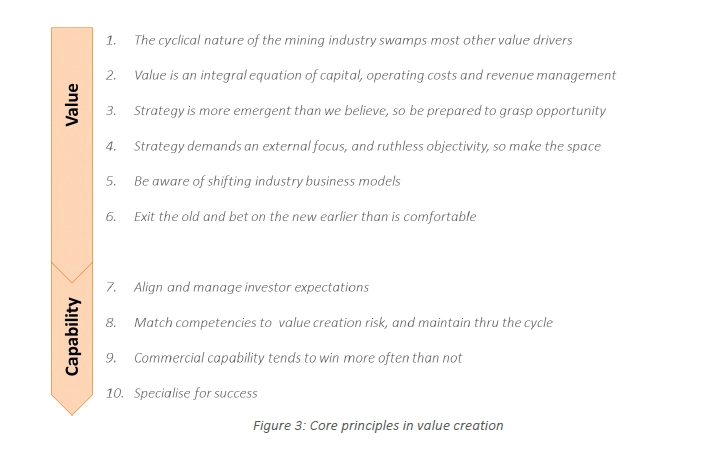

Given the inherent uncertainty of the external environment over the long time frames considered in mining investments, the potentially very large “bets” typically made, and the inherent susceptibility of decision makers to psychological biases (Stanway, Hart & Taylor, 2013), articulating and holding firm on a key set of principles which guide strategic decision making is critical. Combining collective experience in mining, with well-established value creation principles outlined by successful investors and economists (Galbraith, 1990), (Hagstrom, 2004), (Marks, 2011), the following principles are offered:

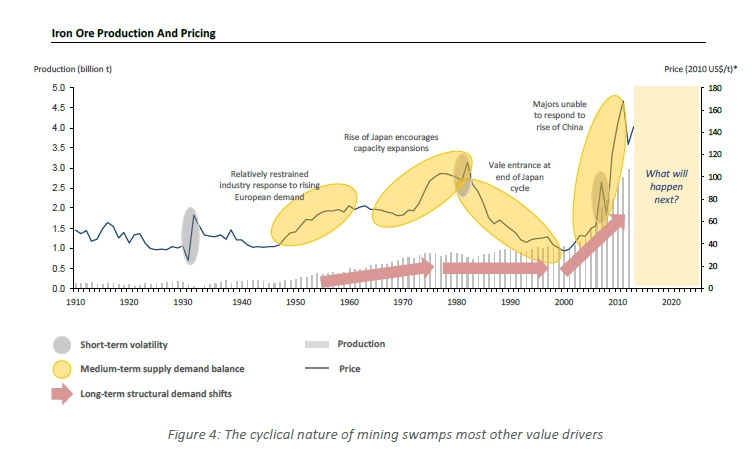

1. The cyclical nature of mining swamps most other value levers

“Rule number one: most things will prove to be cyclical. Rule number two: some of the greatest opportunities for gain and loss come when other people forget rule number one.” (Marks)

Mining is a naturally cyclical industry. Economic development drives demand, and because of its capital intensive nature, supply inevitably lags and this puts pressure on prices. However, because there is ultimately no shortage of minerals, supply is incentivized (most often too much), and prices revert (and usually overshoot). The recent China driven boom is just another example of others that have preceded, and the landing is also likely to be similar. As with the tech boom of the early 2000’s one should be wary of claims of a “new era” and “structural shifts to higher prices”. The quote above captures this succinctly. The implication of cycles is that variations in asset prices and therefore business value, tends to swamp all other forms of value. There is no shortage of examples. The key is to be very sceptical about buying in the up cycle (Figure 4) as there are rarely bargains to be had, and maintain the financial strength, and commitment to invest in the down cycle. Paradoxically, investor psychology, is usually to perceive risk when investing in the down cycle, whereas the opposite is true.

2. Value is an integrated equation of capital, operating costs and revenue management

“Most investors think quality, as opposed to price is the determinant of whether something is risky… But high quality assets can be risky, and low quality assets can be safe” (Marks)

Many mining businesses can be overly consumed with operating costs. This can lead to buying low cost (i.e. high quality) assets without sufficiently emphasising the entry price, and in operation, running the business at the lowest possible operating costs without sufficiently emphasizing the value available through revenue management. Value (and risk) needs seen as an integrated equation of capital (the entry price), operating efficiency (the cost of operation) and revenue management (the ability to optimise price).

The strong emphasis on operating cost is probably a combination of the sheer mass of leadership and execution activity in this area, the fact that it is believed to be more controllable than other factors, and because it is immediately measurable. However, capital expenditure and revenue related decisions are sometimes not afforded the level of scrutiny and skilled assessment in terms of benefit and risk commensurate with its value impact, when in many instances this can be larger than operating leverage. Revenue management in particular in many mining companies is opaque and lack accountability. Marketing functions are often set up as “clearing houses” and can be prone to adopting discounting approaches which move product, leaving value on the table. There is a good reason why trading companies are currently out-bidding operators in asset acquisitions, and that is because they recognise the value that is not being realised in the market by some miners.

3. Strategy is more emergent than we believe, so be prepared to grasp opportunity

Strategy researchers (Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, 2008), and most entrepreneurs recognize that strategy is heavily emergent. That is, a broad direction is set and key competencies focused on, but the ultimate strategic pathway is heavily impacted by unpredicted opportunities and business impacts.

To prosper in this environment, businesses need to be “patiently opportunistic”. This means having a leadership culture which is open and sufficiently agile to act on high value opportunities which emerge. It also means having the discipline not to act impulsively when opportunities do not meet predetermined value criteria. Critical to success is a clear view of the intrinsic value of potential assets within the firm’s field of interest (as broad as possible), with this value being determined using objective external price scenarios. Patient opportunism also requires having the resources and balance sheet to act – this means acting on low value high costs options has a major opportunity cost, as this depletes the ability to act when great opportunities present.

4. Strategy demands external focus and ruthless objectivity, so make the space

All credible strategy starts with an external focus. However organisations naturally tend to become more in-ward looking over time, and unfortunately this is either exacerbated by good performance (no need to change, i.e. look externally), or when the business is under severe threat (no time to look externally, just need to get balance sheet sorted). Also, the sheer weight of operational focus in mining companies tends to anchor an internal perspective.

The remedy is fairly simple, but often counter cultural. The strategy activity should be given space and the remit (from the Chairman and CEO) to look externally, and challenge the status quo (including hierarchical norms) in search of objectivity. It should inform, but not be hard wired to the planning process, which by necessity is convergent and inward looking. To accommodate effective strategy, some businesses deliberately separate Executive processes into parallel Op. Co and Strat. Co. processes, with the latter being infused with more regular external challenge.

5. Be aware of shifting industry business models

Business models in mining are likely to undergo significant change in the next few years. This view is shared by executives in the industry (Stanway & Andrew, 2013) and tangible signals support this view. For example, commodity traders (Meersman, Rechtsteiner, & Sharp, 2012) hampered by low returns and possessing superior market based commercial skills (to miners), are increasingly moving into asset ownership creating a new category of mining company. Other signals indicating pending business model change include the large amount of private equity and sovereign money that is being assembled for investment in the Mining industry, in anticipation of asset buying opportunities as China slows.

A change in business models through this next industry phase would not be a new phenomenon; in fact it is to be expected and has happened before. For example, Rio Tinto pioneered asset investment selection and achieved stellar performance through the lower growth era of the 1980’s and early 90’s, while Xstrata shifted from a relatively small operator at the turn of the century to a major, diversified mining company through its strategy of active asset acquisition as demand for resources surged. For their time, both of these models were innovative, and the respective businesses reaped the benefits.

6. Exit the old and bet on the new earlier than is comfortable

The business world is littered with examples of companies that saw the future, perhaps ahead of many others, but became anchored in their current assets and could not make the switch to this future. Kodak invented the digital camera but stuck with film; Xerox invented the laptop and GUI interface but stuck with copiers, and the American iron and steel industry was an early partner in Australian and South American iron ore but stayed at home. One can speculate whether the Australian and Brazilian iron ore producers will similarly fail to take full advantage of the West African potential.

The message is that the left to its own devices, the dominant existing culture will always tend to prevent the full development potential of new businesses which are a step change from the current, simply because these new businesses will always be viewed through existing lenses. Mining companies’ need a divestiture strategy as well as an acquisition strategy. Also paradoxically companies’ strongest assets may over time, be a hindrance to diversifying successfully.

7. Align and manage investor expectations

Institutional investors’ dominate the share register of most publically listed mining companies. Post the GFC these investors have moved, almost in unison, towards a perspective which places a high premium on cash generation, and which is wary of large capital developments given the associated risk. The reticence to support large expansions in the mining industry is also fuelled by the fact that many institutional investors have holdings in each of the major mining companies and are cognoscente of what increased capacity will do to their investment returns across the sector as a whole.

These sentiments make strategies other than those focused on cost reduction and productivity of existing assets challenging to sell to shareholders. For an executive to respond slavishly to this pressure and not fully explore and promulgate value adding, growth opportunities would be an abrogation of responsibility. It would also probably lead to high value countercyclical opportunities being overlooked in the next few years and sow the seeds of a continuation of the damaging pro-cyclical behaviour that many companies fall into.

8. Match competencies to value creation risk, and maintain through the cycle

Strategy is as much about competencies as it is about choosing direction. For example, to some mining companies operating in West Africa is seen as high risk, but to others which have developed the competencies to operate there it is a natural source of value opportunity. To other companies developing complex Greenfield process plants is seen as high risk, but to others with deep engineering culture this is seen as a source of opportunity.

There is a tendency to attempt to deal with risk analytically in capital evaluation processes by such mechanisms as increasing investment hurdle rates by a few percentage points for developing countries, or allocating increased project contingency for complex greenfield projects. However, in reality, risk is more binary with a higher spread often asymmetric and incalculable than these analysis techniques would suggest. That is, if the competency is deeply aligned with the initiative, risk is much lower than assumed and vice versa.

9. Commercial capability tends to win more often than not

There is a notable list of examples where business who have excelled at operational excellence, have ultimately ceded significant value in deals with companies with a sharper focus on commercial opportunity, and particularly market timing.

One only has to look at many of the high profile mergers and acquisitions over the last two decades and compere the revenue contribution of assets bought to the deal by each side at the time of merger, and the relative contribution of assets today. There is a consistent pattern, where the revenue contribution today is far less from the merging party who bought “commercial acumen” to the table compared with the merging party who bought “operating excellence” to the table. That is, the natural deal makers ultimately received a far higher relative valuation for their assets at the long term expense of the other share-holders.

The value accretion associated with these examples to the more commercial entities is staggering and outweighs most other value sources discussed in this paper. It is also therefore highly sensitive. The conclusion, therefore, is that while operating capability is essential, it is a mining company’s commercial gaming acumen that will very often determine its value creation success.

10. Specialise for success

The combination of globalization, technology, and aggressive competition is driving the need for companies to specialise to succeed. That is, very successful companies focus on only a few core competencies where they can be truly leading. However, the trap that many companies fall into is an expectation of being near or above benchmark capability across the board, which adds costs, reduces agility, reduces focus, and all without delivering a value creating advantage.

There are several questions mining companies therefore need to answer:

- Where does it have (or is close to having) existing competitive advantage?

- Given its strategy, what few additional competencies must it develop?

- Is it prepared to make the change required to deliver these new competencies?

Developing and implementing value-creating strategy

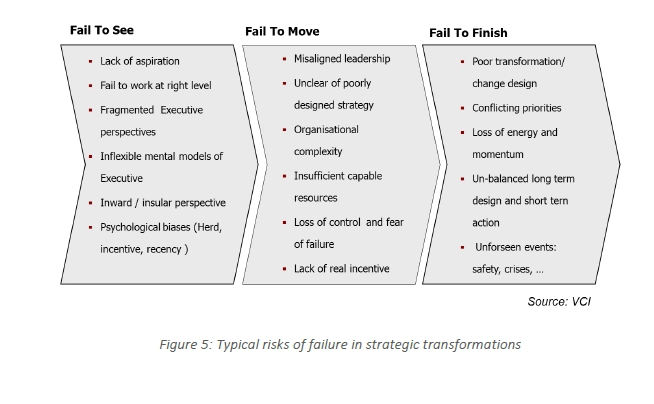

Most strategic transformations fail because either the strategy is not appropriate for the challenges faced (fail to see), or if the strategy is appropriate the business does not act (fail to move), or the business cannot simply sustain the effort required to achieve transformation (fail to finish). Typical, but non-exhaustive causes of these failures are outlined in Figure 5.

Therefore, in addition to the complex intellectual work required to answer the “what” question in relation to value creation, to achieve success, the business must also deliberately ask, and answer the important process based “how” questions, related to implementation:

- How will the strategy be developed (what is the process and the role of key players)?

- How will alignment and commitment be achieved within senior leadership team

- How will the critical strategic programs be resourced, designed and delivered?

- How will the integrated transformation process be a sustainable program and change managed?

- How will strategy be managed dynamically reviewed given the world is not static?

In the end, the “what” and the “how” are hardly divisible – that is; strategy and change are opposite sides of the same coin.

References

- Galbraith, J (1990). A Short History of Financial Euphoria. Penguin

- Geoscience Australia. (2012). Australian Gas Resource Assessment 2012. Australian Government.

- Hagstrom, R. (2004).The Warren Buffett Way. John Wiley & Sons.

- IMF. (2013). Government Net & Gross Debt. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/01/weodata/index.aspx

- Marks, H. (2011). The Most Important Thing. Columbia University Press.

- Meersman, S., Rechtsteiner, R., & Sharp, G. (2012). The Dawn Of A New Order In Commodity Trading. Oliver Wynman.

- Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., & Lampel, J. (2008). Strategy Safari: The complete guide through the wilds of strategic management. Pearson Education Canada.

- PressTV (2013). Real crisis is not government shutdown. Retrieved from http://www.presstv.com/detail/2013/10/03/327316/real-crisis-is-not-government-shutdown/

- Stanway, G., & Andrew, D. (2013). Mining Innovation State of Play 2013. Virtual Consulting International.

- Stanway, G., Hart, W., & Taylor, C. (2013). Overcoming Biases in Strategy Formulation. Virtual Consulting International.

This article was originally published at Mine Insider.