Why are you still using cattle prices to forecast graded beef cuts?

Published: March 20, 2023

“What’s been going on with the beef price forecast?” Sound familiar?

Since COVID, pricing models at the cut level don’t seem to work anymore. We know why and we know how to restore accuracy to cut level beef price forecasting.

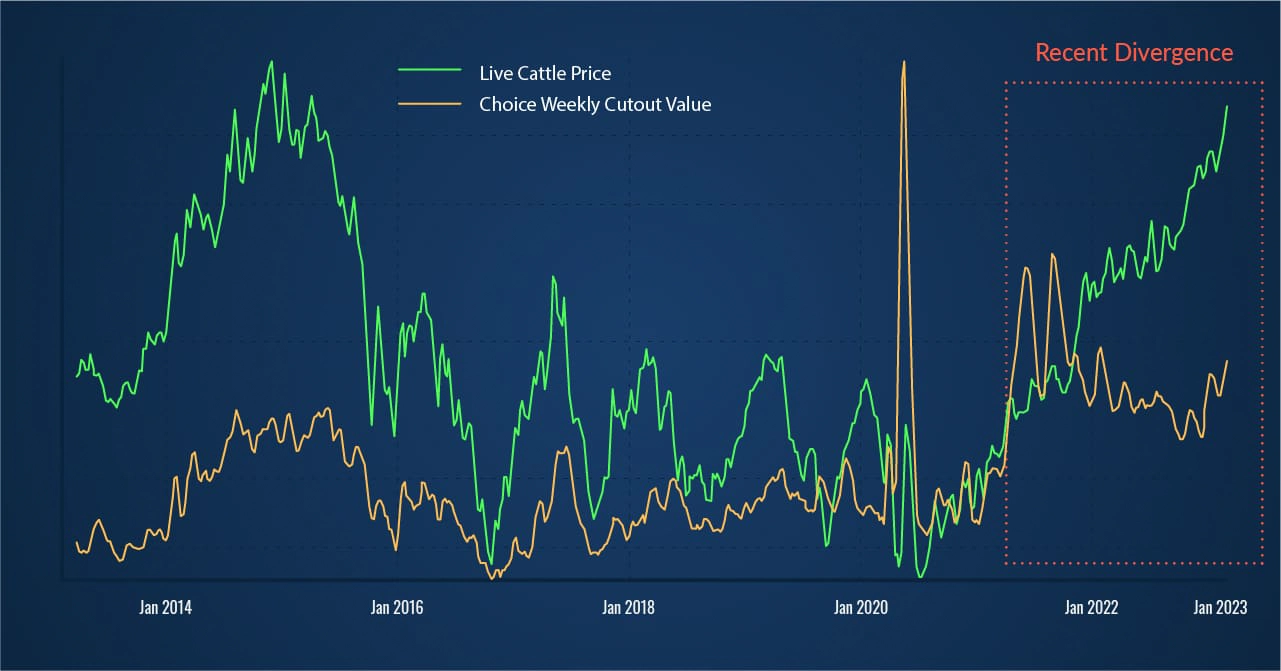

Standard beef cut ratios to cattle price just don’t hold up anymore. A series of factors, including increased demand for higher grades of beef and skyrocketing feed costs, have shattered the correlation between cattle prices and beef prices (Fig. 1), forcing us to reconsider methodologies for modeling beef prices.

Figure 1 - Graph illustrating the historical correlation and recent divergence between live cattle prices and weekly beef cutout values

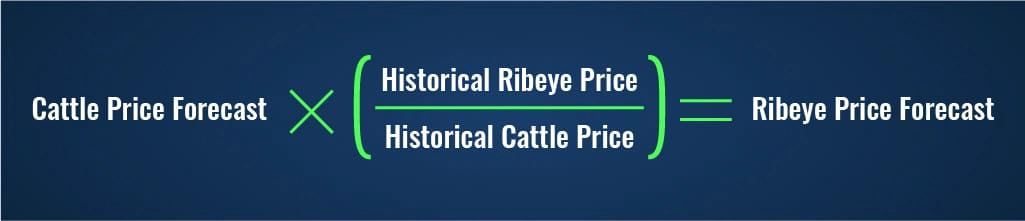

It is time for the industry to re-examine the standard ratio to cattle price approach to forecasting beef prices. How does that classic cattle price ratio model work? First, the modeler forecasts cattle prices. This could mean using the CME forward curve as the cattle forecast, or could mean using a predictive model based on fundamentals, machine learning, or any other forecasting methodology. After the modeler has their cattle price forecast, they need to calculate a ratio for a specific cut to that cattle price. This could be a three year average ratio, or a more sophisticated approach which takes into account how these ratios change seasonally or year-to-year. Then the modeler multiplies the cattle price forecast on a given future date by the ratio forecast on that same date, to get a price forecast for a specific cut of beef on a specific date.

Figure 2 - Cattle Price to Cut Ratio Model

Figure 2 - Cattle Price to Cut Ratio Model

This approach has been the standard in the industry for decades and it offers a lot of benefits, especially for market participants who need to calculate hedge positions or want to maintain some consistency between their forecasts for hundreds of individual cuts. That said, the change we’ve witnessed over recent years in the relationship between cattle and beef prices has degraded the accuracy of the cattle price ratio model as a method to predict beef prices. In other words, the old ratio forecasting approach is not useful anymore. To be fair, how can a method developed decades ago be expected to work well in today’s volatile markets? A lot has changed…

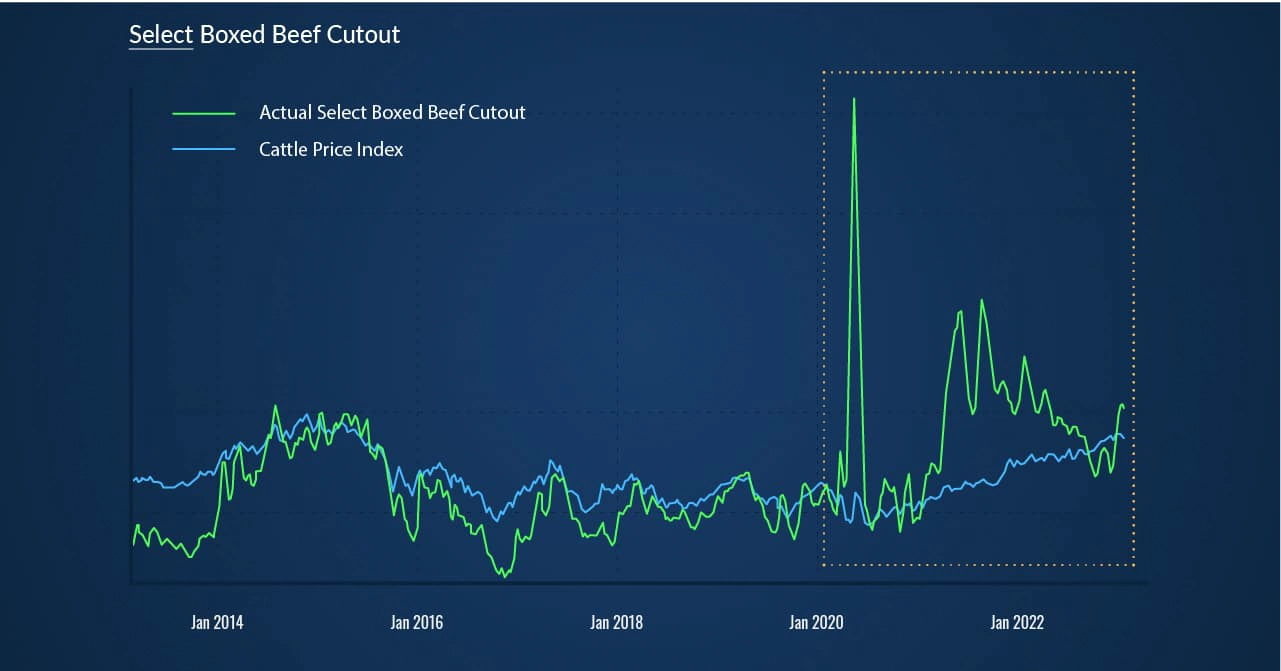

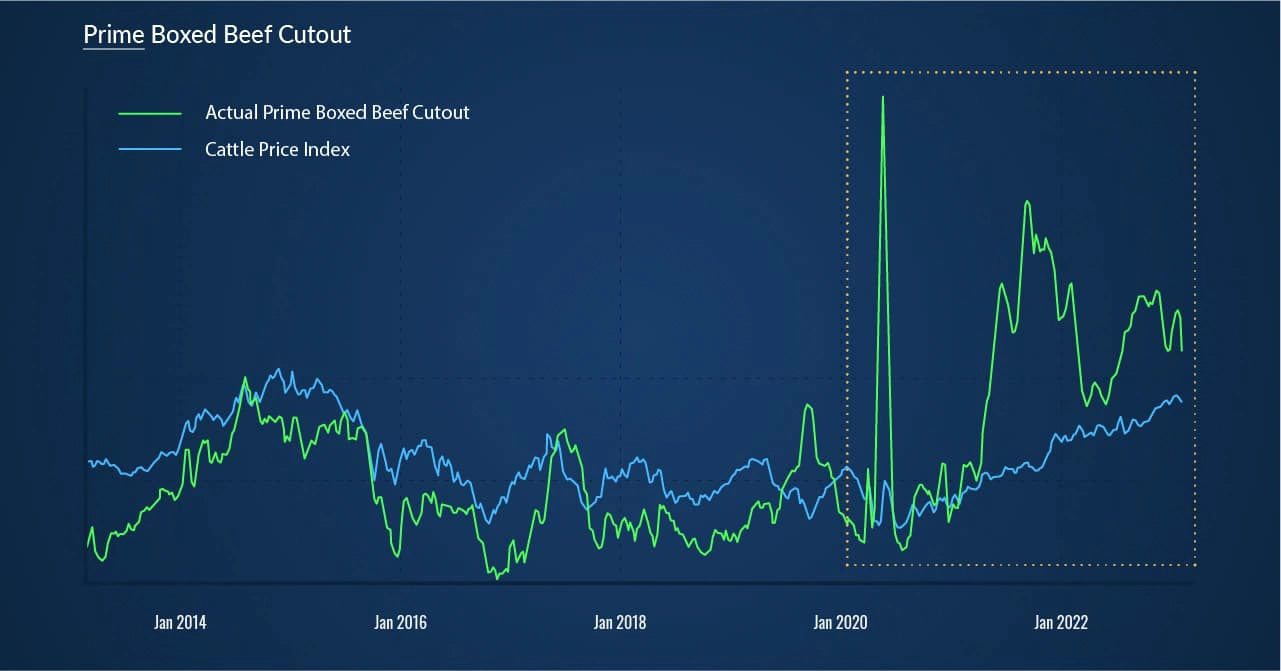

In the two charts below we see how cattle prices have compared to cutout prices over time. In the “Select Box Beef Cutout” chart (Fig. 3) there has been a very noticeable correlation between the two over time – until the Covid pandemic hit. At that point the two lines seemed to disengage. Interestingly, if you look at the second chart below, the “Prime Box Beef Cutout” (Fig. 4) you will see the same disengagement at the time of the pandemic… but it actually precedes the pandemic. Note that in late 2019 the prime cutout (the green line) spikes upward, indicating higher prices for prime cuts, while fed cattle prices are falling. So this is a bigger story than just the pandemic; changes in consumer behavior show consumers upgrading their purchases from select to choice, and choice to prime, driving up the prime cutout.

Figure 3 - Graph illustrating the historical correlation of the select boxed beef cutout and cattle price index.

Figure 3 - Graph illustrating the historical correlation of the select boxed beef cutout and cattle price index.

Figure 4 - Graph illustrating the historical correlation of the prime boxed beef cutout and cattle price index.

Figure 4 - Graph illustrating the historical correlation of the prime boxed beef cutout and cattle price index.

OK, back to our ratios! So if the fed cattle price is no longer a good index to multiply by a ratio to predict beef prices, is there another number we can use instead? It turns out there is. A much stronger relationship has existed in recent years between boxed beef prices and the boxed beef cutout. And the relationship is stronger still if this is done by grade (a graded cut of beef vs. the graded cutout). During a period defined by volatile macroeconomic conditions, the graded cutout is more reflective than cattle price of the supply and demand for specific beef cuts – and it is therefore more reflective of their price.

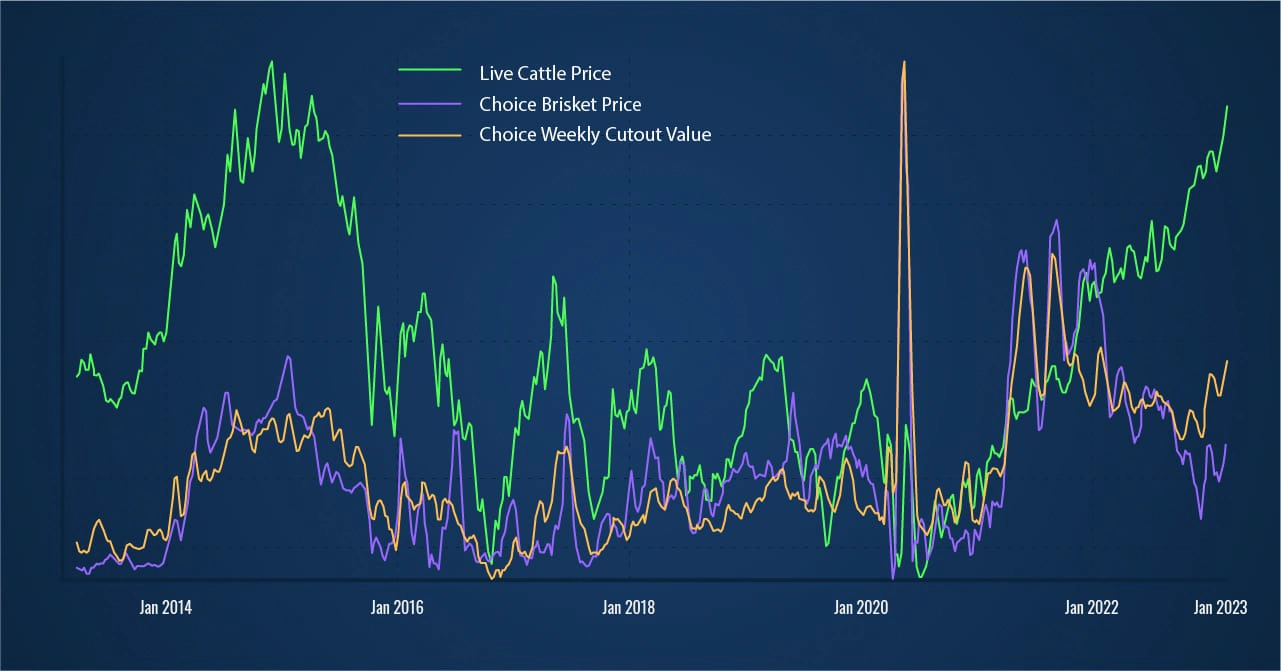

Notice that that when we plot fed cattle price (the green line) against the choice cutout (the brown line) and then overlay brisket prices (the purple line), what we’ve been talking about in the white paper is clear: there’s a much greater correlation between the cut and the cutout, than between the cut and fed cattle (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 - Choice brisket price relationship to choice cutout overlaid on top of the live cattle price

Figure 5 - Choice brisket price relationship to choice cutout overlaid on top of the live cattle price

In summary, we’ve established that the approach of forecasting boxed beef prices by using a ratio to some common underlying forecast is good, since it creates consistency among the hundreds of beef prices that need to be forecasted. But we’ve also shown that the historical practice of using the fed cattle price to do this is flawed, because the fed cattle price has become disconnected from boxed beef prices in recent years (Fig. 5).

Happily, we have found another forecastable price that is much better correlated to boxed beef prices: the cutout. Forecast errors using cutout are significantly lower than when using fed cattle, and the best news yet is that forecast errors reduce even further when these forecasts are done by grade.

You wouldn’t use corn futures to predict a cut of beef, there’s just not enough correlation between the two goods. So why are you still using cattle to forecast the price of a prime striploin?

It’s time to make a change.